I. Introduction: A New Dawn for Indian Agriculture

The story of Indian agriculture is one of profound resilience, yet it remains tethered to the vagaries of nature and the inefficiencies of infrastructure. For decades, the Indian farmer has navigated a complex landscape of challenges, from unpredictable monsoons to the high costs of energy required for irrigation. This energy dilemma has historically presented a stark choice: for those in off-grid areas, a costly dependence on diesel pumps, and for those connected to the grid, an unreliable power supply, often at odd hours, that strains both farm operations and the finances of state power distribution companies (DISCOMs).

- I. Introduction: A New Dawn for Indian Agriculture

- II. The Grand Vision: Core Objectives of PM-KUSUM

- III. Deconstructing PM-KUSUM: A Three-Pronged Strategy

- IV. The Financial Blueprint: Subsidies, Loans, and Farmer Contribution

- V. From Policy to Practice: The Application Roadmap for Farmers

- Important Advisory: Beware of Fraudulent Websites

- VI. Impact on the Ground: Voices from the Field

- VII. Navigating the Hurdles: A Critical Analysis of Implementation Challenges

- VIII. The Path Forward: The Future of PM-KUSUM

- IX. Conclusion: Cultivating a Sustainable and Prosperous Future

- X. FAQs

- XI. Disclaimer

In response to this multifaceted crisis at the intersection of agriculture, energy, and water, the Government of India launched a landmark initiative. In March 2019, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) unveiled the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) scheme.

More than a mere subsidy program, PM-KUSUM represents a paradigm shift in rural policy, encapsulating the vision of transforming the nation’s farmers from ‘Annadata’ (food providers) to ‘Urjadata’ (energy providers). This ambitious mission aims to solarize the agricultural sector, providing farmers with a reliable and affordable source of clean energy for irrigation while creating opportunities for them to generate additional income.

The scheme’s strategic importance extends beyond the farm gate. It is a cornerstone of India’s commitment to its Intended Nationally Determined Contributions (INDCs) under the Paris Agreement, aiming to increase the share of installed electric power capacity from non-fossil-fuel sources to 40% by 2030. Despite initial implementation hurdles, the government has demonstrated its long-term commitment by extending the scheme’s timeline to March 31, 2026.

A surface-level view might categorize PM-KUSUM as simply a solar pump scheme. However, a deeper analysis reveals it to be a sophisticated, multi-sector reform initiative. Its objectives and design are interwoven to simultaneously address agricultural distress by enhancing farmer income, reform the energy sector by improving the financial health of DISCOMs, and advance national climate goals by de-dieselising the farm sector.

This intricate architecture, which necessitates coordination between central ministries, state energy agencies, DISCOMs, and agriculture departments, is both the source of its transformative potential and the root of many of its implementation challenges. This report provides an exhaustive analysis of the PM-KUSUM scheme, dissecting its objectives, components, financial structure, and real-world impact, while critically examining the hurdles that lie on the path to realizing its full potential.

PM-KUSUM Scheme at a Glance

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Full Scheme Name | Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan |

| Launch Date | March 2019 |

| Nodal Ministry | Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) |

| Stated Objectives | Energy & water security, income enhancement, de-dieselisation, environmental protection, improving DISCOM health |

| Target Solar Capacity | 34,800 MW by March 2026 |

| Total Financial Outlay | ₹34,422 crore |

| Scheme Extension Date | March 31, 2026 |

II. The Grand Vision: Core Objectives of PM-KUSUM

The PM-KUSUM scheme is built upon a foundation of four interconnected objectives, each designed to address a critical vulnerability in India’s rural economy and energy landscape. Understanding these goals is essential to appreciating the scheme’s holistic approach.

1. Providing Energy and Water Security

At its core, PM-KUSUM is an energy security mission for farmers. For decades, agricultural productivity has been hampered by unreliable power. Farmers with grid connections often receive electricity during off-peak, nighttime hours, making irrigation inconvenient and hazardous. Those without grid access are at the mercy of volatile diesel prices. The scheme directly confronts this by providing a dependable, daytime source of solar power for irrigation. This reliability not only enhances agricultural productivity by enabling timely watering but also improves the quality of life for farmers, freeing them from nocturnal irrigation schedules and the constant worry of fuel availability.

2. Enhancing Farmer Income

A key innovation of PM-KUSUM is its transformation of farmers into prosumers—producers as well as consumers of energy. The scheme enhances farmer income through two distinct pathways:

- Significant Cost Savings: By replacing diesel pumps, farmers can save a substantial amount on fuel costs, estimated to be around ₹50,000 per year for a 5 HP pump. For those with grid-connected pumps, solarisation leads to a drastic reduction or complete elimination of electricity bills. This frees up capital that can be reinvested into the farm, improving yields and livelihoods.

- Direct Revenue Generation: The scheme creates new, stable income streams. Under Component A, farmers can lease their barren or fallow land to developers for setting up solar plants, earning a steady annual rent for 25 years. Estimates suggest this could range from ₹25,000 to ₹65,000 per acre per year. Under Components A and C, farmers can sell surplus electricity generated by their solar installations directly to the grid, creating a reliable source of secondary income.

3. De-dieselising the Farm Sector and Reducing Carbon Footprint

The agricultural sector is a significant contributor to India’s diesel consumption and, consequently, its carbon emissions. PM-KUSUM’s objective to de-dieselise the farm sector is a direct environmental intervention. By promoting the replacement of millions of diesel-powered irrigation pumps with clean solar alternatives, the scheme aims to reduce harmful air and water pollution associated with burning fossil fuels. This transition not only contributes to a healthier rural environment but also aligns with India’s national and international commitments to combat climate change.

4. Improving the Financial Health of DISCOMs

India’s power distribution companies are caught in a financially precarious position, largely due to the burden of providing subsidized or free electricity to the agricultural sector. This erodes their financial health and hampers their ability to invest in grid modernization. PM-KUSUM addresses this systemic issue in two ways. Firstly, by solarising agricultural pumps, it reduces the amount of subsidized power DISCOMs need to supply, directly lowering their subsidy burden. Secondly, Component A promotes decentralized power generation, where electricity is produced close to the point of consumption in rural areas. This significantly reduces the transmission and distribution (T&D) losses that DISCOMs incur when transmitting power over long distances from centralized power plants.

The scheme’s design masterfully creates a virtuous cycle where these objectives reinforce one another. For instance, under Component C, farmers are incentivized to sell surplus power to the grid. This financial incentive is a powerful tool for behavioral change. To maximize the surplus power available for sale, a farmer must use energy—and by extension, water—more efficiently. This directly counters the tendency for over-extraction of groundwater, a severe environmental problem often exacerbated by the flat-rate or free electricity tariffs prevalent in agriculture. The power sold by the farmer is then purchased by the local DISCOM, helping it meet its mandatory Renewable Purchase Obligation (RPO) targets and reducing its own financial losses. In this way, the farmer’s pursuit of additional income is ingeniously aligned with the state’s goals of water conservation and the DISCOM’s need for financial stability, demonstrating a sophisticated policy design that seeks to solve multiple challenges through a single, market-linked mechanism.

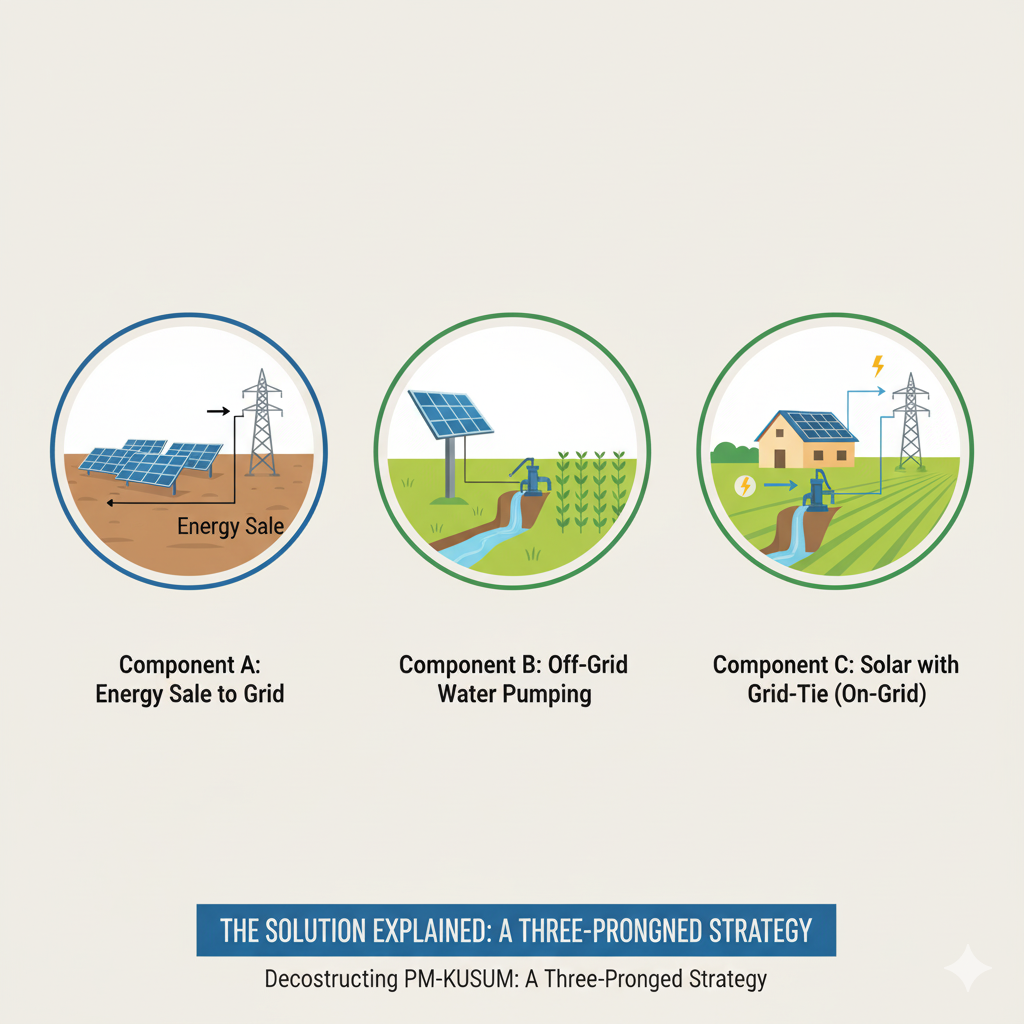

III. Deconstructing PM-KUSUM: A Three-Pronged Strategy

The PM-KUSUM scheme is not a monolithic program but a carefully structured strategy with three distinct components, each tailored to the diverse energy access profiles and needs of India’s farming community. This segmented approach is a key strength, allowing for targeted interventions whether a farmer is completely off-grid, poorly served by the grid, or has the potential to become a power producer.

Component A: Farmers as Power Producers (Decentralized Power Plants)

Component A embodies the most ambitious aspect of the ‘Urjadata’ vision, enabling farmers and rural communities to become small-scale power producers.

- Mechanism: This component targets the installation of 10,000 MW of decentralized, grid-connected renewable energy power plants (REPPs). Individual projects can range in capacity from 500 kW to 2 MW, making them small enough to be integrated into the rural distribution network without requiring major grid upgrades.

- Location and Land Use: To ensure efficiency, these plants are to be installed within a five-kilometer radius of a local electricity sub-station, which minimizes transmission losses and connection costs. A significant innovation is the flexibility in land use. Plants can be set up on barren or fallow land, turning unproductive assets into revenue-generating ones. Furthermore, they can be installed on cultivable land using stilt-mounted structures. This practice, known as agrivoltaics, allows crops to be grown underneath the solar panels, thus avoiding the “food versus fuel” conflict over land use.

- Financial Model: This component operates without direct capital subsidies for the farmer. Instead, the financial incentive is built around a long-term, stable revenue stream. The power generated is purchased by the local DISCOM under a 25-year Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) at a pre-determined Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) set by the respective State Electricity Regulatory Commission (SERC). To encourage DISCOMs to procure this power, the central government provides them with a Procurement Based Incentive (PBI) of 40 paise per kWh for the first five years. For farmers who cannot invest themselves, the scheme allows them to lease their land to a developer and earn a fixed annual rent.

Component B: Energy Independence for Off-Grid Farms (Standalone Pumps)

Component B is a direct intervention aimed at farmers who are most acutely affected by energy poverty—those in off-grid areas with no access to electricity and a complete dependence on expensive and polluting diesel pumps.

- Mechanism: The component aims to support the installation of 14 Lakh standalone solar agricultural pumps. These systems operate independently of the electricity grid, providing farmers with energy self-sufficiency for their irrigation needs.

- Target Beneficiaries: This component is specifically designed for individual farmers in off-grid or unreliable grid areas to replace their existing diesel pumps. The guidelines prioritize small and marginal farmers, as well as those who have adopted micro-irrigation techniques like drip or sprinkler systems, to promote water efficiency alongside energy transition.

- Pump Capacity: The scheme provides financial support for pumps with a capacity of up to 7.5 HP. While farmers can install higher capacity pumps, the Central Financial Assistance (CFA) is capped at the 7.5 HP level. Recognizing the unique geographical and agricultural needs of certain regions, this limit is extended to 15 HP for farmers in North-Eastern states, hilly regions, and island territories.

Component C: Solarising the Grid-Connected Farmer (Grid-Connected Pumps)

Component C targets the largest segment of farmers—those who already have an electric pump connected to the grid but suffer from unreliable and poor-quality power supply. It aims to solarize 35 Lakh such pumps through two distinct but complementary approaches.

- Individual Pump Solarisation (IPS): Under this sub-component, individual farmers can install a solar panel system on their land to power their existing grid-connected pump. The guidelines permit the installation of a solar PV capacity up to two times the pump’s capacity in kilowatts. This “oversizing” is a critical design feature. It allows the farmer to use the generated solar power to meet their irrigation needs during the day and export the surplus power to the grid. This surplus power is then purchased by the DISCOM at a pre-fixed tariff, creating a second income stream for the farmer and turning an energy expense into a revenue source.

- Feeder Level Solarisation (FLS): This is a more recent and innovative addition to the scheme. Instead of solarising individual pumps one by one, the FLS model involves solarising an entire agricultural feeder—the dedicated power line that supplies electricity to a group of farms in a locality. A single, larger solar power plant is set up to meet the entire electricity demand of that feeder. This provides all farmers connected to it with reliable, high-quality, daytime power for irrigation, either free of cost or at a tariff fixed by the state. This approach, which can be implemented under either a CAPEX (upfront investment) or RESCO (developer-owned) model, offers economies of scale and simplifies the process of grid integration for the DISCOM.

This three-component structure reveals a tiered and sophisticated strategy. Component B is the foundational level, addressing the basic need for energy access for the most deprived, off-grid farmers. Component C is the intermediate level, targeting the vast number of under-served, grid-connected farmers and transforming their relationship with the grid from one of passive consumption to active production. Component A represents the highest tier, creating opportunities for farmers with sufficient land and resources to become rural energy entrepreneurs. The provision allowing states to transfer allocated quantities between Component B and Component C adds a layer of flexibility, enabling them to tailor the scheme’s implementation to their specific demographic and energy landscape.

Comparative Analysis of PM-KUSUM Components

| Component | Component A | Component B | Component C (IPS & FLS) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Group | Farmers, FPOs, Cooperatives, Developers with land | Off-grid farmers, primarily using diesel pumps | Farmers with existing grid-connected pumps |

| Primary Objective | Generate revenue by selling power to the grid | Provide energy access for irrigation, replace diesel | Improve power reliability and generate income from surplus power |

| Technology Used | Decentralized solar power plants (500 kW – 2 MW) | Standalone solar pumps (up to 7.5 HP) | Grid-tied solar systems for individual pumps or entire feeders |

| Grid Interaction | Sells all power to the grid under a PPA | Completely off-grid | Uses solar power for self-consumption, sells surplus to the grid |

| Income Model | Revenue from FiT for 25 years or land lease rent | Cost savings on diesel | Cost savings on electricity bills and revenue from selling surplus power |

| Key Financial Support | Procurement Based Incentive (PBI) for DISCOMs | 60-80% subsidy on system cost | 60-80% subsidy on system cost |

IV. The Financial Blueprint: Subsidies, Loans, and Farmer Contribution

The financial architecture of the PM-KUSUM scheme is designed to make the transition to solar energy accessible and affordable for farmers across different economic strata. The model primarily relies on a combination of central and state subsidies, coupled with institutional finance, to significantly reduce the upfront investment required from the beneficiary.

Subsidy Structure for Components B and C

For the installation of standalone solar pumps (Component B) and the solarisation of grid-connected pumps (Component C – IPS), the scheme operates on a standard tripartite cost-sharing model :

- Central Financial Assistance (CFA): The Government of India provides a subsidy of 30% of the benchmark cost of the system or the cost discovered through tenders, whichever is lower.

- State Government Subsidy: The respective state government is required to provide a matching subsidy of at least 30%.

- Farmer’s Contribution: The beneficiary farmer is responsible for the remaining 40% of the cost.

To further ease the financial burden, the scheme facilitates access to bank loans. Farmers can avail an agricultural term loan to cover up to 30% of the total system cost. This crucial provision means that the farmer’s actual upfront, out-of-pocket contribution can be as low as 10% of the total cost, making the technology highly accessible. To ensure that banks are encouraged to lend for this purpose, the scheme has been included under the Reserve Bank of India’s Priority Sector Lending (PSL) guidelines, and major banks like the State Bank of India (SBI) have formulated specific loan products for PM-KUSUM beneficiaries.

Enhanced Support for Special Category States

Recognizing the unique challenges and difficult terrains in certain parts of the country, the scheme provides a higher level of central support for North-Eastern States, Sikkim, Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and the island territories of Lakshadweep and Andaman & Nicobar. In these regions, the financial structure is modified as follows :

- Central Financial Assistance (CFA): Increased to 50% of the benchmark cost.

- State Government Subsidy: Remains at a minimum of 30%.

- Farmer’s Contribution: Reduced to the remaining 20%.

Financial Model for Component A

Unlike the direct capital subsidies of Components B and C, the financial model for Component A (decentralized power plants) is indirect. There is no upfront subsidy provided to the farmer or developer for setting up the plant. Instead, the financial viability is ensured through a long-term revenue guarantee:

- Guaranteed Power Purchase: DISCOMs are mandated to purchase the power generated from these plants for 25 years at a Feed-in-Tariff (FiT) determined by the state regulator.

- Procurement Based Incentive (PBI): To make this power procurement financially attractive for the often-strained DISCOMs, the central government provides them with a PBI of 40 paise per kWh or ₹6.60 lakhs per MW per year (whichever is less) for the first five years of the plant’s operation.

Flexibility in Implementation

The scheme’s guidelines also include a crucial flexibility clause. In cases where a state government is unable to provide its 30% share of the subsidy, the scheme can still be implemented. Under this scenario, the central government’s 30% CFA remains available, and the farmer’s share increases to cover the remaining 70%.

While the financial model’s design to bring the upfront cost down to 10% is its greatest strength, making it theoretically accessible to all, this very structure also represents its primary vulnerability. The model’s success is critically dependent on the timely and efficient functioning of two external pillars: the fiscal health of state governments to disburse their subsidy share, and the willingness of the rural banking sector to extend credit. As implementation has shown, the “availability of low-cost financing for farmers and state share of funds is a major challenge”. The reluctance of banks to fund these projects and delays in subsidy disbursement from states have become significant bottlenecks, leading to the wide regional disparities seen in the scheme’s uptake. The flexibility clause allowing implementation with a 70% farmer share, while well-intentioned, places a prohibitive burden on most farmers, rendering the scheme unviable in states with weak finances.

Financial Assistance Breakdown for PM-KUSUM Components B & C

| Source of Funding | General States (%) | Special Category States (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Central Govt. (CFA) | 30 | 50 |

| State Govt. Subsidy | 30 | 30 |

| Farmer’s Share (Total) | 40 | 20 |

| Farmer’s Upfront Share (with loan) | 10 | 10 |

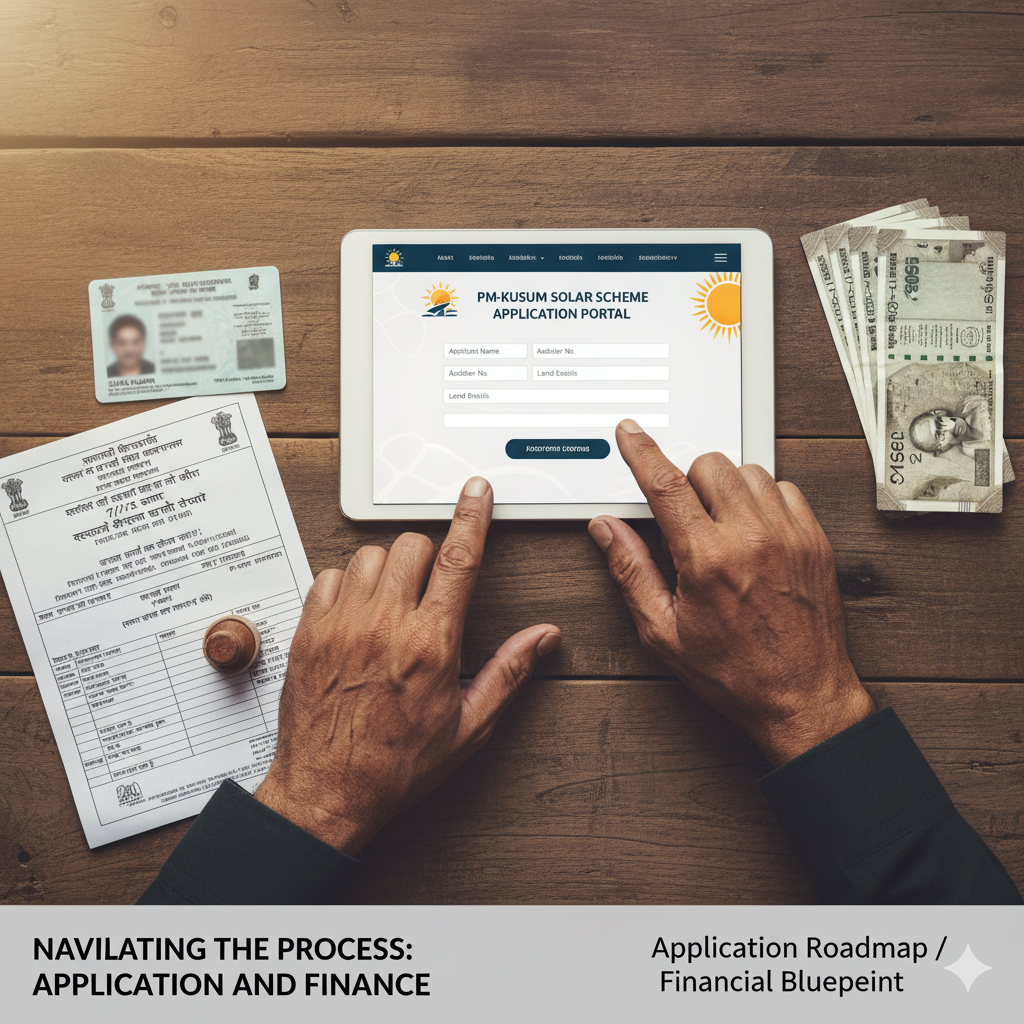

V. From Policy to Practice: The Application Roadmap for Farmers

Navigating the application process for a government scheme can often be daunting. This section provides a clear, step-by-step guide for farmers wishing to avail the benefits of PM-KUSUM, outlining the eligibility criteria, application procedures, and necessary documentation.

Eligibility Checklist

Before starting the application, farmers should ensure they meet the eligibility criteria for the desired component:

- Component A (Decentralized Power Plants): Eligibility is broad, extending to individual farmers, groups of farmers, cooperatives, Panchayats, Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), and Water User Associations (WUAs). The most critical technical requirement is that the proposed land for the project must be located within a 5-kilometer radius of the nearest electricity sub-station.

- Component B (Standalone Solar Pumps): This is open to individual farmers, WUAs, and community or cluster-based irrigation systems located in off-grid areas where there is no reliable grid supply.

- Component C (Grid-Connected Solar Pumps): Applicants must be individual farmers, WUAs, or part of a community irrigation system who already have an existing grid-connected agricultural pump.

Step-by-Step Application Process

The application process is primarily online, designed to streamline submissions and improve transparency.

- Visit the Official Portal: The first and most crucial step is to access the correct website. Applicants must use either the national PM-KUSUM portal (pmkusum.mnre.gov.in) or the designated portal of their respective state’s implementing agency.

- Online Registration: On the portal, locate the “Apply” or “Registration” section. Fill in the initial registration form with basic details like name, mobile number, and address to create an account.

- Fill the Detailed Application Form: After logging in, select the specific component (A, B, or C) you are applying for. Proceed to fill out the detailed online application form, providing accurate information about your land, existing pump (if any), and bank details.

- Upload Required Documents: Scan and upload clear copies of all the necessary documents as specified on the portal. Ensure the files are in the required format and size.

- Submit and Track Application: After reviewing all the details, submit the application form. You will receive an application reference number, which should be saved for future use. This number can be used to track the status of your application on the portal.

- Post-Approval Formalities: Once your application is verified and approved, you will be notified by the state implementing agency. For Components B and C, you will be required to deposit your beneficiary contribution (typically 10% of the cost) with the designated vendor or agency. The installation of the solar system will commence after the subsidy amount is formally sanctioned.

For farmers who are not comfortable with the online process, an offline option may be available. They can visit the nearest office of the state’s Agriculture Department or the designated implementing agency to obtain and submit a physical application form.

Documentation Checklist

To ensure a smooth application process, farmers should have the following documents ready :

- Identity Proof: Aadhaar card is mandatory.

- Land Documents: Proof of land ownership, such as Khasra Khatauni, Record of Rights (RTC), or Patta.

- Bank Account Details: A copy of the bank account passbook to verify account details for subsidy transactions.

- Declaration Form: A self-declaration form, as prescribed by the agency.

- Contact Information: An active mobile number.

- Photograph: A recent passport-sized photograph.

- Electricity Bill (for Component C only): A copy of the latest electricity bill for the existing grid-connected pump.

Important Advisory: Beware of Fraudulent Websites

The Ministry of New and Renewable Energy has issued multiple warnings about fake websites that fraudulently claim to be registration portals for the PM-KUSUM scheme. These sites often have domain names similar to the official scheme name and are designed to dupe applicants into paying fake registration fees or to misuse their personal data.

- ALWAYS use the official national portal: https://pmkusum.mnre.gov.in/

- For state-specific applications, verify the portal link through the official MNRE website.

- For any queries or clarifications, contact the official toll-free helpline number: 1800-180-3333.

- The government does not charge any fees for simply submitting an application form. Fees, if any, are only payable after official sanction and through designated channels.

While the digitization of the application process is intended to enhance efficiency, it has inadvertently created new challenges. The process is often perceived as “complicated” by farmers, leading to significant “delays in application processing” and approvals. This administrative friction not only frustrates applicants but also makes them more vulnerable to the numerous fraudulent schemes that promise faster processing for a fee. The prevalence of such scams underscores a critical gap in digital literacy and last-mile support. It suggests that for the scheme to be truly inclusive, the digital interface must be complemented by robust offline support systems, such as dedicated helpdesks at block-level agricultural offices and widespread, multi-lingual awareness campaigns to guide farmers safely through the legitimate application process.

VI. Impact on the Ground: Voices from the Field

The true measure of any policy lies in its real-world impact on the lives of its intended beneficiaries. The PM-KUSUM scheme, since its inception, has generated a diverse range of outcomes, from transformative success stories to frustrating tales of bureaucratic delay. These experiences from the field provide invaluable insights into the scheme’s strengths and weaknesses.

Case Study 1 (Component A): Smt. Rewati Devi, Alwar, Rajasthan

Smt. Rewati Devi’s story is a powerful testament to the ‘Urjadata’ vision of Component A. A resident of Sanoli village in Rajasthan’s Alwar district, she successfully commissioned a 2 MW capacity solar power plant on her land in June 2021. Her experience encapsulates the scheme’s potential to create rural energy entrepreneurs. She states, “I am really happy with my decision of getting a solar plant installed under PM KUSUM. We are able to get the generation of six units per kilowatt on clear sunny days and now we have a reliable source of income”. Her case demonstrates how barren or underutilized land can be converted into a long-term, revenue-generating asset, providing a stable income independent of agricultural cycles.

Case Study 2 (Component B): Smt. Sumitra Devi, Mahendragarh, Haryana

In Bhagadhana village, Haryana, Smt. Sumitra Devi’s experience highlights the direct agricultural benefits of Component B. She had a 5-acre farm but was constrained by the high running cost of her diesel pump. “I used to cultivate only one crop,” she recalls.

After learning about the PM-KUSUM scheme, she applied and had a 10 HP solar pump installed, benefiting from a combined 75% subsidy from the central (30%) and Haryana state (45%) governments. The impact was immediate and profound. “Now I can cultivate more than one crop and irrigate the fields in the daytime. Besides, there is no cost of running and the maintenance cost of the solar pump is negligible. I am very satisfied,” she reports. Her story is a textbook example of how the scheme achieves its goals of de-dieselisation, reduced input costs, and enhanced agricultural productivity.

Broader Impact Analysis

Beyond individual testimonials, broader studies and reports corroborate these positive impacts:

- Significant Income Enhancement: Research indicates that farmers adopting solar pumps have seen their annual incomes increase by anywhere from 23% to as high as 83% in certain regions of Rajasthan. The opportunity to sell surplus electricity provides a substantial revenue stream, with some reports citing farmers earning as much as ₹4 lakh per month from their solar plants.

- Increased Agricultural Productivity: The availability of reliable, daytime power for irrigation has a direct impact on farm output. Studies have documented an increase in cropping intensity, allowing farmers to grow multiple crops per year, and a significant rise in crop yields, which have reportedly doubled in some cases after the installation of a solar pump.

The Counter-Narrative: A Tale of Delays and Disillusionment

However, the journey for many farmers has been far from smooth. Testimonials from Madhya Pradesh paint a starkly different picture, one of bureaucratic inertia and financial distress. Rajendra Singh Chauhan, a farmer from Rajgarh district, applied for a 0.5 MW solar plant in 2020. Years later, he was still entangled in paperwork. During this delay, the project cost escalated from approximately ₹3.5 crore to ₹4.5 crore. “The banks aren’t ready to give us the loan on the revised cost and are offering a loan on the previous cost,” he laments. Another farmer, Shubham Roy, faced a similar situation with his 1 MW plant application, where a two-year delay led to a ₹1 crore cost increase, making the project financially unviable even before it started. These experiences highlight a critical failure in the implementation chain, where administrative delays and an inflexible financing mechanism have eroded farmer trust and turned a promising opportunity into a financial nightmare.

These contrasting experiences reveal a crucial truth about the PM-KUSUM scheme: its success is highly localized and contingent on the efficiency and proactiveness of state-level implementation. The generous 45% state subsidy in Haryana, which exceeded the mandatory 30%, significantly lowered the barrier to entry for farmers like Smt. Sumitra Devi. Conversely, the administrative quagmire in Madhya Pradesh created insurmountable financial hurdles for its applicants. This demonstrates that while the national framework of PM-KUSUM provides the blueprint, the ultimate outcome for a farmer is determined less by the policy’s design and more by the administrative capacity and financial commitment of their respective state government and its implementing agencies.

VII. Navigating the Hurdles: A Critical Analysis of Implementation Challenges

Despite its transformative potential and numerous success stories, the implementation of the PM-KUSUM scheme has been fraught with challenges, leading to a significant gap between its ambitious targets and on-ground achievements. As of May 2025, a staggering 94% of the 10,000 MW target under Component A remained uninstalled. While Component B has seen more widespread adoption, the grid-connected components (A and C) have witnessed “minimal implementation” in many regions. A critical analysis of these hurdles is essential for understanding the scheme’s uneven performance and for charting a more effective path forward.

Financial Barriers

The financial structure, while designed to be accessible, has proven to be a major obstacle.

- High Upfront Costs: Even with subsidies, the farmer’s contribution of 20-40% represents a substantial upfront investment that is often beyond the means of small and marginal farmers, who are a key target group.

- Difficulty in Accessing Credit: This is perhaps the single most critical bottleneck. Despite the inclusion of the scheme under priority sector lending, farmers consistently report extreme difficulty in securing bank loans. Banks are often reluctant to finance these projects due to perceived risks, lack of collateral, or unfamiliarity with the technology, effectively stalling the application process for farmers who cannot self-finance their share.

Administrative and Policy Bottlenecks

Bureaucratic inertia and policy misalignments have significantly slowed down the scheme’s pace.

- Procedural Delays: A common complaint from farmers is the inordinate delay in application processing, subsidy sanctioning, and the signing of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) by DISCOMs. These delays can stretch for years, leading to cost escalations that render projects unviable.

- Unattractive Tariffs: Under Component A, the financial viability for a farmer or developer depends on the tariff offered by the DISCOM. In many states, the pre-fixed or bid-discovered tariffs have been too low to provide an attractive return on investment, discouraging participation.

- Centralized Implementation Models: Some states have adopted a highly centralized implementation model, which sidelines local agencies that possess better on-ground knowledge of farmer needs and regional conditions. A decentralized approach, where different agencies handle components based on their expertise, has been suggested as more effective.

Technical and Operational Issues

On-the-ground technical and service-related problems have also emerged post-installation.

- Performance in Adverse Weather: A majority of beneficiaries (over 76%) report that solar panels do not function effectively during cloudy, rainy, or winter days, affecting the reliability of irrigation during crucial periods.

- Quality and Maintenance: There are widespread concerns about the inferior quality of some solar panels and water pumping systems supplied under the scheme. This is compounded by a lack of proper and timely post-installation maintenance services from empanelled vendors, leaving farmers stranded with non-functional equipment.

Ground-Level Realities and Awareness Gaps

The scheme’s success also depends on navigating the complex socio-economic realities of rural India.

- Lack of Awareness and Proliferation of Fraud: A significant number of farmers remain unaware of the scheme’s details, application procedures, and benefits. This information vacuum has been exploited by malicious actors, leading to a proliferation of fraudulent websites and scams that dupe farmers into paying fake fees.

- Security Concerns: In remote rural areas, the security of the installed equipment is a major issue. Beneficiaries report frequent instances of solar panel theft and damage caused by wildlife, such as monkeys, adding an unexpected layer of risk and cost.

A deeper analysis reveals a fundamental policy conflict that undermines the scheme’s adoption, particularly for Component C. In many states, farmers have long received free or heavily subsidized electricity for agriculture. While this power is unreliable, its near-zero cost creates a powerful disincentive to invest in a solar system, even a heavily subsidized one. From a farmer’s economic perspective, the effort and upfront investment required for PM-KUSUM may not seem justified when the alternative is perceived as “free.” The scheme is therefore not just competing with diesel; it is competing with the deeply entrenched political economy of farm power subsidies. Overcoming this hurdle requires either a politically sensitive reform of the subsidy regime or making the financial returns from PM-KUSUM so compelling that they decisively outweigh the allure of free grid power.

PM-KUSUM Implementation Challenges and Proposed Solutions

| Challenge Category | Specific Problem | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Financial | High upfront cost for farmers | Allow payment of farmer’s contribution in installments; Increase subsidy amount in high-cost regions. |

| Financial | Difficulty in accessing bank loans | Streamline loan processes; create dedicated financing cells; enforce Priority Sector Lending targets for KUSUM. |

| Administrative | Delays in application processing & approvals | Establish single-window clearance portals; set strict timelines for DISCOMs and state agencies. |

| Administrative | Unattractive tariffs for Component A | Rationalize tariff-setting to ensure project viability for developers and farmers. |

| Technical | Poor quality of equipment | Enforce stricter quality control standards for empanelled vendors; conduct third-party audits. |

| Technical | Lack of maintenance services | Make 5-year mandatory maintenance contracts more robust and enforceable; establish local service centers. |

| Awareness & Security | Low awareness and vulnerability to fraud | Launch widespread, multi-lingual awareness campaigns through local media and agricultural extension networks. |

| Awareness & Security | Theft and damage to panels | Promote community-based security models; include protective fencing/measures in the project cost. |

VIII. The Path Forward: The Future of PM-KUSUM

Despite the implementation hurdles, the future of the PM-KUSUM scheme appears poised for evolution rather than stagnation. The government’s decision to extend the scheme to March 2026 signals a firm commitment to its long-term vision. Furthermore, the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) is actively preparing for a “Phase 2,” often referred to as “PM-KUSUM 2.0,” which is expected to incorporate the critical learnings from the initial phase and introduce more scalable and effective models.

Integration of Technology and Smart Grid Concepts

The future of PM-KUSUM is increasingly intertwined with digital technology and smart grid concepts. The initial focus on deploying hardware is gradually shifting towards creating an intelligent, manageable network of distributed energy resources.

- Smart Monitoring and Control: The mandatory inclusion of a Remote Monitoring System (RMS) in every solar pump is a foundational step. This is now evolving with a push from the MNRE to adopt more advanced IoT-based SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) systems. These systems allow for the real-time collection of performance data from thousands of dispersed solar plants and pumps, enabling efficient management, fault detection, and performance optimization from a centralized dashboard. This data-driven approach is crucial for ensuring asset reliability, maximizing generation, and automating processes like billing and subsidy disbursement.

- Grid Modernization and Stability: The scheme, particularly through Feeder Level Solarisation (FLS), is acting as a catalyst for modernizing India’s rural electricity grid. By injecting clean power directly into the distribution network during the daytime, these projects help reduce the load on agricultural feeders, improve voltage stability, and provide DISCOMs with a better tool to manage their daytime power demand.

- Maximizing Asset Utilization: To address the issue of solar pumps lying idle for large parts of the year, the scheme supports the use of Universal Solar Pump Controllers (USPCs). A USPC allows the solar panel to power other electrical appliances—such as chaff cutters, flour mills, or battery chargers—when it is not being used for pumping water, thereby maximizing the utilization of the solar asset and providing additional value to the farmer.

The Promise of Agrivoltaics

One of the most exciting future directions for PM-KUSUM is the promotion of agrivoltaics. The scheme’s provision for installing solar plants on stilt-mounted structures over cultivable land is a direct endorsement of this innovative concept. Agrivoltaics, or the dual use of land for agriculture and solar energy generation, offers a powerful solution to the land-use conflict. Research and pilot projects have shown that this symbiotic relationship can be mutually beneficial. The partial shade from the solar panels can reduce water evaporation and protect certain crops from excessive heat, sometimes even leading to higher yields for shade-tolerant crops like moong bean and cumin. For farmers, this means they can continue their agricultural activities while earning a separate, stable income from energy generation on the same piece of land, effectively doubling its productivity.

Policy Evolution and Recommendations

Learnings from the first phase are shaping key policy recommendations for accelerating the scheme’s deployment in its next iteration:

- Financial Innovations: To overcome the upfront cost barrier, proposals include allowing farmers to pay their contribution in easy installments rather than a lump sum and providing targeted, higher subsidies in regions with specific challenges.

- Institutional Streamlining: A key recommendation is the creation of a National Digital KUSUM Portal. Such a platform could integrate GIS data on sub-station capacities, available land parcels, and water table levels, creating a one-stop-shop for planning, application, and monitoring, thereby cutting through administrative red tape.

- Scalable Models: The success of utility-led, aggregated models for feeder solarization, as demonstrated by states like Maharashtra, offers a replicable template. These models leverage economies of scale, simplify land acquisition, and provide a more streamlined implementation pathway compared to aggregating thousands of individual farmers.

This evolution indicates a significant maturation in the scheme’s philosophy. PM-KUSUM is transitioning from being a simple hardware subsidy program to becoming a technology-enabled, data-driven rural energy platform. The focus is shifting from merely distributing assets to creating an intelligent, interconnected ecosystem of energy generation and consumption that can be optimized for the mutual benefit of the farmer, the community, the DISCOM, and the environment. This represents a far more sophisticated and sustainable vision for India’s agricultural energy future.

IX. Conclusion: Cultivating a Sustainable and Prosperous Future

The Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM) scheme stands as one of the most ambitious and visionary policy interventions in modern Indian agriculture. It was conceived not merely as a solution to a single problem but as a holistic strategy to untangle the complex, decades-old knot binding agricultural distress, energy insecurity, and environmental degradation. Its dual mission—to empower farmers economically by turning them into energy producers and to simultaneously advance India’s national energy security and climate goals—is both bold and essential.

The analysis reveals that the scheme’s core principles are fundamentally sound. By providing a pathway to reduce crippling input costs, create stable new revenue streams, and ensure a reliable supply of clean energy, PM-KUSUM holds the undeniable potential to transform rural livelihoods and landscapes. The voices from the field, from farmers now cultivating multiple crops to those earning a steady income from previously barren land, offer compelling proof of this potential.

However, the journey from policy design to on-ground reality has been uneven and fraught with significant challenges. The gap between sanctioned targets and commissioned projects points to deep-seated hurdles in financing, administration, and last-mile execution. The scheme’s success has been highly dependent on the fiscal health and administrative agility of state governments, creating a patchwork of progress across the country. Financial institutions have been slow to embrace this new market, and procedural delays have tested the patience and finances of many aspiring beneficiaries.

Yet, these challenges should not be viewed as a failure of the vision, but as invaluable feedback for its refinement. The government’s commitment to extending the scheme and preparing for a “PM-KUSUM 2.0” reflects an understanding that such a large-scale transformation requires continuous learning and adaptation. The future of the scheme lies in addressing its current weaknesses head-on: by streamlining access to credit, decentralizing implementation, leveraging technology for greater transparency and efficiency, and resolving the policy conflict with existing power subsidies.

Ultimately, the journey to transform India’s farmers from ‘Annadata’ to ‘Urjadata’ is a marathon, not a sprint. The success of PM-KUSUM will be measured not just by the megawatts installed, but by its ability to cultivate a new ecosystem of energy independence, economic prosperity, and environmental stewardship, farm by farm, village by village. It requires a sustained, collaborative effort from all stakeholders—central and state governments, financial institutions, technology providers, and the farmers themselves—to ensure that this powerful vision takes firm root and flourishes across the Indian agricultural landscape.

X. FAQs

What is the full name and primary goal of the PM-KUSUM scheme?

The full name is Pradhan Mantri Kisan Urja Suraksha evam Utthaan Mahabhiyan (PM-KUSUM). Launched in March 2019 by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE), its main objectives are to provide energy and water security to farmers, increase their income, shift the farm sector away from diesel, and reduce environmental pollution.

What are the three main components of the PM-KUSUM scheme?

The scheme is divided into three parts :

- Component C: Solarisation of existing grid-connected agriculture pumps.

- Component A: Setting up decentralized grid-connected solar power plants of 500 kW to 2 MW capacity.

- Component B: Installation of standalone solar-powered agriculture pumps in off-grid areas.

Who is eligible to apply for the PM-KUSUM scheme?

Eligibility is broad and includes individual farmers, groups of farmers, Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), cooperatives, Panchayats, and Water User Associations (WUAs). Specific eligibility depends on the component you are applying for.

What is Component A and who can benefit from it?

Component A involves setting up small solar power plants (500 kW to 2 MW) on barren, fallow, or agricultural land. The power generated is sold to the local electricity distribution company (DISCOM). This allows farmers or rural landowners to earn a stable income for 25 years by either installing the plant themselves or leasing their land to a developer.

What is Component B and who is it for?

Component B is for farmers in off-grid areas who rely on diesel pumps for irrigation. It supports the installation of new, standalone solar agriculture pumps up to 7.5 HP, providing a reliable and clean energy source for irrigation without dependence on the grid or diesel.

What is Component C and how does it work?

Component C is for farmers who already have a grid-connected electric pump. It involves installing solar panels to power these existing pumps. A key feature is that farmers can install a solar capacity up to twice their pump’s capacity, use the power for irrigation, and sell any surplus electricity back to the grid, creating an additional income source.

What is the difference between Individual Pump Solarisation (IPS) and Feeder Level Solarisation (FLS)?

Both fall under Component C.

- FLS is a larger-scale approach where an entire agricultural feeder (the power line supplying a group of farms) is solarised with a single power plant. This provides reliable daytime power to all farmers on that feeder.

- IPS is when an individual farmer solarises their own grid-connected pump.

How much subsidy is available for solar pumps under Components B and C?

For most states, the government provides a total subsidy of 60% of the benchmark cost. This is typically split between the Central Government (30%) and the State Government (30%).

What is the farmer’s upfront contribution, and can I get a loan?

After the 60% subsidy, the farmer is responsible for the remaining 40%. However, the scheme facilitates bank loans for up to 30% of the cost, which means the farmer may only need to pay 10% as an upfront contribution. The scheme is included under the RBI’s Priority Sector Lending guidelines to make it easier to get loans.

Is there a higher subsidy for farmers in certain regions?

Yes. For North-Eastern states, Sikkim, Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and island territories, the Central Government’s subsidy (CFA) is increased to 50%. With the state’s 30% contribution, the farmer’s share is reduced to just 20%.

How do I apply for the PM-KUSUM scheme?

The application process is primarily online. You must visit the official national PM-KUSUM portal (pmkusum.mnre.gov.in) or the designated portal of your state’s implementing agency, register, fill out the application form, and upload the required documents. An offline option may be available at the local agriculture department office.

What are the main documents required for the application?

Commonly required documents include an Aadhaar card, proof of land ownership (like Khasra Khatauni), a bank account passbook, a declaration form, and a passport-sized photograph. For Component C, a copy of your latest electricity bill is also needed.

There are many websites for PM-KUSUM. How can I avoid scams?

This is a serious issue. The MNRE has warned about numerous fake websites that illegally ask for registration fees. To be safe, only use the official national portal: pmkusum.mnre.gov.in. For any doubts, you can also call the toll-free helpline at 1800-180-3333.

What are the direct benefits for a farmer who installs a solar pump?

The main benefits include :

- Improved Agriculture: Better water availability can lead to higher crop yields and the ability to grow more crops per year.

- Reduced Costs: Eliminates spending on diesel and reduces or ends electricity bills.

- Reliable Power: Provides a dependable source of power during the daytime for irrigation.

- Increased Income: Opportunity to sell surplus power back to the grid (under Components A and C).

Can I really earn money from this scheme?

Yes. Under Component A, you can earn a steady income for 25 years by selling all the power generated to the DISCOM or by leasing your land. Under Component C, you can earn money by selling surplus electricity that is not used for irrigation.

What are the environmental benefits of the PM-KUSUM scheme?

The scheme promotes sustainable agriculture by reducing the carbon footprint of the farm sector. By replacing diesel pumps, it cuts down on harmful pollution. By providing an incentive to sell surplus power, it can also discourage the over-extraction of groundwater.

What happens on cloudy or rainy days? Will the pump work?

This is a common challenge. The performance of solar panels is significantly reduced during cloudy, rainy, or foggy weather, which can affect the pump’s operation. The system is most effective on clear, sunny days.

Who is responsible for the maintenance of the solar equipment?

For Components B and C, the vendor who installs the system is typically required to provide a mandatory 5-year maintenance contract (AMC). However, some farmers have reported issues with receiving timely and proper maintenance services.

What is the current deadline for the PM-KUSUM scheme?

The scheme has been extended and is scheduled to run until March 31, 2026.

Where can I find a list of state-level agencies and approved vendors?

The official national PM-KUSUM portal (pmkusum.mnre.gov.in) maintains lists of state-wise implementing agencies, state portal links, and empanelled vendors along with their rate cards.

XI. Disclaimer

This article is an independent analysis and is not an official publication by any government body, including the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) or any state implementing agencies. The information presented herein has been compiled through in-depth online research from a wide array of sources to provide a comprehensive and informative overview of the PM-KUSUM scheme. While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, readers are advised to consult official government portals for the most current guidelines, application procedures, and specific details. Information has been sourced from various public domains, including official government websites.